05.02.2025 | Sergi Gonzàlez Herrero | SLF News

SLF scientist Sergi González-Herrero is conducting research in Antarctica for two months. From there, he regularly reports in Catalan for the Catalan Foundation for Research and Innovation (FCRI) to get young students aged between twelve and sixteen involved in science. The SLF also publishes his articles.

During the last few days, I've been on a small expedition. In fact, I went about 200 kilometers north to the Antarctic coast. My objective: to do a snow measurement transect. My companions on the trip were Paula, a chemical engineer who studies pollutants in snow, and Manu, the polar guide who was dedicated to driving, setting up camp and helping us. We went on this expedition with a special snow car called Hilux. The distances, which would be a matter of hours in a “normal” place, becomes very long in Antarctica. This is because vehicles can only go between 15 and 25 kilometers per hours depending on visibility and snow conditions. Here you can see a map with the route.

The trip started with very good weather, but as we advanced north, visibility began to decrease due to the fog that is typical in coastal areas. First the sun began to fade, and then a solar halo appeared. Solar haloes are optical phenomena that occur when high, thin clouds move in front of the sun. When we saw the solar halo, it felt like floating inside a cloud. As we advanced, everything became more and more white until white was the only colour we could see anymore.

“Whiteout” is the name given to the phenomenon that occurs in snowy places, when high clouds or fog appear, and everything turns completely white, and you can’t distinguish the ground from the sky. Not even the horizon is discernible anymore. It’s a very confusing meteorological phenomenon, you lose all your bearings, you don’t know if you’re going up or down, you can move without realizing it. The only way to orientate ourselves was with the weak GPS signal and our route.

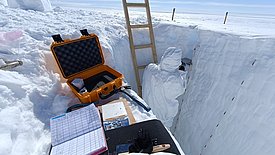

Finally, after many hours of driving, we arrived at the main measurement point at 8 pm. Both Paula and I needed to dig through 2.5 meters of snow. I took physical measurements of the snow (temperature and density), and Paula took some samples. Thes samples, however, needed to get to the ship. Luckily, we had two colleagues who had arrived earlier who would go back there to deposit the samples in two days. Since the weather was very tight, that same night (remember that in Antarctica there is no night in the summer) we started digging a two-and-a-half-meter snow profile, which is equivalent to removing more than one thousand kilograms of snow. During the dig, the weather was quite bad because the wind was blowing snow the whole time and there was no visibility. We finished at twelve, snowed in and freezing and then went to sleep in the camp that Manu had set up while we were digging.

The next day we got up very early – it was a beautiful day that day – and we were finally able to see the coast thirty kilometers away. We could spot some floating icebergs in the coastline. However, there was not too much time to marvel at the views because duty called: we had only one day left to take all the measurements of the snow profiles. Since Paula needed to measure the chemical components of the snow, we had to put on a special suit so as not to contaminate it and change its composition. Then we started sampling. We finished at around one in the morning before we finally got to rest. But that rest was even more replenishing, knowing that all the work had finally been done.

The next morning our colleagues left with the samples, and we finished the measurements that did not require sampling. We also installed some instruments for Paula. Unfortunately, the poor visibility had returned and did not leave us until we would return to the base. We started the next day with my snow transect. The next point would be much closer to the coast, only five kilometres, where the snow conditions are very different from the rest of Antarctica. After making the measurements we turned around to start heading back towards the Princess Elizabeth station. At that moment I realized that, except for my two companions, the nearest human being was more than 180 kilometres away from us. Imagine, if within in a distance from Zurich to Laussanne there was not a single person near you and the only thing there was, was a frozen desert.

During the 200 kilometres return I dug a snow profile every 50 kilometres, while we moved at 15 kilometres per hour. The slow speed was attributed to the “sastrugi”, the irregularities of the snow that look like dunes in the desert. Even though they are beautiful, they made the trip quite uncomfortable and tiring. At this speed it took us two days to reach the station again. Already near the station the weather finally improved and the lenticular clouds of the mountains, the low orange sun and the snow crawling on the ground gave us one of the most beautiful views we had yet seen of this continent.

Already published: ¶

Copyright ¶

WSL and SLF provide image and sound material free of charge for use in the context of press contributions in connection with this media release. The transfer of this material to image, sound and/or video databases and the sale of the material by third parties are not permitted.