19.02.2025 | Sergi Gonzàlez Herrero | SLF News

SLF scientist Sergi González-Herrero is conducting research in Antarctica for two months. From there, he regularly reports in Catalan for the Catalan Foundation for Research and Innovation (FCRI) to get young students aged between twelve and sixteen involved in science. The SLF also publishes his articles.

We are reaching the end of the expedition. I have everything set up and have started packing up what remains here and what returns to Switzerland.

Being in the southern hemisphere, means that I am experiencing the opposite season of Switzerland – here it is currently summer. Being so far south, we do not have day and night cycles, the sun revolves around us, and it is always daytime. However, we are already at the end of summer, and it is beginning to be noticeable that the sun at “night” is lower and that the temperatures are starting to be lower. We even saw the first moon of the season over the horizon yesterday.

Soon, almost all the scientists in Antarctica will leave, and only a few scientists and technicians will remain in some stations to do, what we call, “the wintering”. In winter, temperatures plummet, down to -40ºC here, and down to -80ºC or less on the Antarctic plateau, and it is clearly not a very pleasant place to be.

At our latitudes, we are starting to notice increasingly milder and shorter winters because of climate change. But is climate change noticeable in a place as cold as Antarctica? Antarctica is the continent where the effect of climate change have been noticed later than in other places. This is due to several factors. First of all, the temperature records here are among the shortest in the world. The first meteorological series began in 1904 on an island on the Antarctic Peninsula, but it was not until the middle of the 20th century that we began to have real temperature measurements in various parts of the continent. Specifically, since 1957, when the International Geophysical Year was celebrated, which marked the start of the establishment of bases around Antarctica with its meteorological measurements. Without long temperature series we cannot properly understand climate change and therefore this fact has delayed our understanding of the impact of climate change on the continent. Today we continue to make continuous meteorological measurements, both through stations and sounding balloons to measure the vertical structure of the atmosphere. The other day I launched one of these balloons, as you can see in this video:

Another factor that has influenced is the complicated meteorological dynamics of the continent. We are used to the “stable” weather of our home, and it has not been until recently that we have begun to understand more about how the meteorology varies in cold areas. In fact, we still have a lot of research to do to fully understand it. This factor has masked climate change in certain areas of Antarctica until recently. However, in recent years, cases of very severe heat waves have begun to occur in various parts of the continent. In February 2020, the continent's temperature record was broken at a station on the Antarctic Peninsula, reaching a concerning temperature of + 18.3 ºC. In February 2022, the same area repeated went through yet another severe heat wave, and in March of the same year, the interior of Antarctica (one of the coldest areas) experienced a temperature increase of 30 degrees, reaching -10 ºC at the winter beginning. Some scientists like me are investigating these phenomena, and understanding why they occur, since it seems that climate change can manifest itself more severely here.

But where can climate change impact Antarctica most strongly? In the interior of the continent, it can have some effects. For example, some colleagues here near Princess Elizabeth reported some days of ice melting in areas at 2000 m where it had never melted before.

However, the fact that few species live there and that it occurs few times a year means that the impact here may be limited. Where it certainly affects, and a lot, is on the coast. There, temperatures in the summer are around 0 degrees, and a few degrees of warming imply going from negative temperatures where water is in the form of ice to positive temperatures where water is in liquid form. This implies changes in the snow and glaciers, which can melt and make way for habitable areas for new animals and plants.

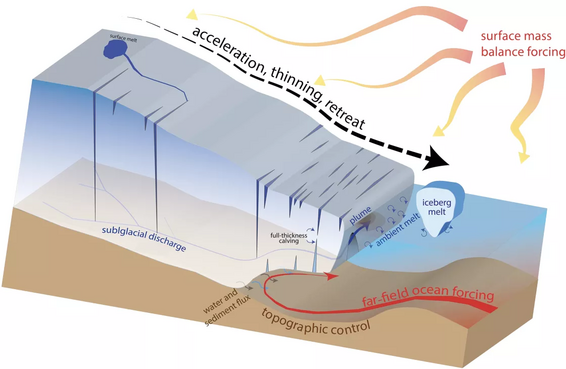

But the real danger is in the ocean. A warmer ocean is starting to melt coastal glaciers, that float on the water, from underneath. We call these glaciers continental ice shelves, and they are what causes icebergs. When icebergs or ice shelves melt, they do not immediately cause a rise in sea level, since floating ice has almost the same density as water. However, ice shelves are a barrier to prevent ice from the continent from penetrating into the sea, and this ice does cause sea level to rise.

Already published ¶

Copyright ¶

WSL and SLF provide image and sound material free of charge for use in the context of press contributions in connection with this media release. The transfer of this material to image, sound and/or video databases and the sale of the material by third parties are not permitted.